- Details

- Hits: 4036

Stress and Relaxation

Dr.Krishna Prasad Sreedhar M.A., Ph.D., D. M & S. P. (NIMHANS)

(2012)

Praveen’s wife telephoned to fix an appointment for counseling. When they came Praveen did not appear very happy about the appointment. He said, “My wife thinks that I need psychological counseling. I do not know for what? She says, of late I am not my old self…I am a changed person. I came just to oblige her”.

I looked at his wife Padma and asked only one question. I wanted to know her educational level because she showed an astonishing insight into the plight of her husband.

Padma politely revealed that she could study only up to the second year degree course. Her marriage made her a house wife. Padma did not have any regrets, for her husband has been very loving and understanding. Her husband has a fat salary and they own a house with all the possible amenities they could imagine.

Padma was waiting to talk. She said “My husband is a brilliant person and is very good at his work. His company raises his salary as soon as they feel that he is planning to go away. Though sometimes he brings his work home, he has always found time to spend with me. Till recently our life was very good. Of late I find him moody and irritated. He finds faults with me for trivial matters. I think he has frequent headaches and stomach upsets, but he refuses to see a doctor. The most upsetting thing is that he is often absent minded and forgets things and feels frustrated. He is tensed up and worries a lot. His sleep is also disturbed and gets up in the morning with a grouchy face…”

I consoled his wife and told that her husband was probably tensed up. I also told her that sincere and hard working people were lot more tensed up these days because of the pace with which life is going on and also competition has become the order of the day. Competition is a threat and produces ‘tension’. Tension either at work or at home makes a person stressed up. While a reasonable degree of stress is a good motivator, in excess it affects the physical, psychological and sociological well being of a person.

I asked the following questions to Praveen and all the answers were in the affirmative.

-

Do you suffer from frequent headaches?

-

Do you have tension at the back of the neck?

-

Do you have a nagging low back ache?

-

Do you experience frequent dryness of mouth and throat?

-

Do you have congestion in the chest?

-

Do you have spells of breathlessness?

-

Do you have frequent trouble with your stomach?

-

Do you have vague aches and pains all over the body?

-

Do you worry a lot about the future?

-

Do you have difficulty waiting to get things done?

-

Do you consider yourself restless of late?

-

Do you get upset when there is commotion around you?

-

Do you have difficulty enjoying things which you used to enjoy?

-

Do you get angry about trivial things and regret later?

-

Do you have difficulty in concentration?

-

Do you have trouble with your memory?

-

Do you feel that you lost your self confidence?

-

Do you often withdraw from social situations?

-

Do you feel that recently you cannot enjoy sex with your wife?

He had all the above problems. At this point his wife nodded as if I hit the most intimate thing in their life. Yes, the intimacy was gone and Praveen has become morose and lonely. (Names have been changed to keep anonymity).

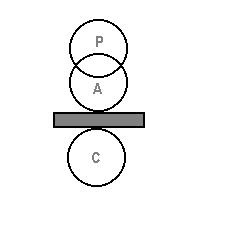

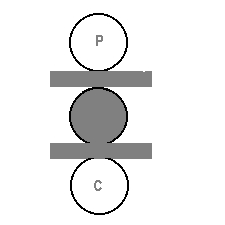

I told him that his wife could be right as he was too tensed up if not stressed up. His work and success unfortunately have put him at a high level of competition to maintain his and his company’s status producing enormous tension and he had no idea of the reward of relaxation. Continuous tension made him experience ‘distress’; the worst form of stress. I explained to him that his trouble was that he has become a victim of bad stress. I also explained to him that stress at an optimum level was not only good but was healthy. However, stress in excess stimulates the brain centers which are primarily responsible for our safety and security – typically known as the flight/fight reaction in which stress hormones are released. Under real threat like standing in front of a furious dog, the release of these hormones are essential as they make our system prepared to fight the dog or escape. However, this life saving mechanism of our psycho physiological system becomes life threatening if it persists in the absence of an objective threat. The flight/fight reaction is a primitive jungle law which used to help the cavemen and animals from dangers. The difficulty with modern men is that they have lots of imagined threats to which the brain reacts more or less the same way when real threat is perceived. Human beings are endowed with the capacity to think verbally and visually. The words and visuals which once threatened a person, often act as real threats forcing the body and mind to react as if the threat is real out there. If these reactions become continuous and chronic, damages occur to our mind and body. The result is chronic tension which manifests as symptoms of undue stress.

Overcoming these stresses is not easy but we can if we make a committed effort. It has been found that people with Type-A personality has more difficulty to come out of undue stresses. By far the best antidote to distress appears to be YOGA. Continuous practice of yoga changes our body metabolism unhealthy attitudes of the mind and a transcendental tranquility.

Those who are disinclined to do yoga may try the modern techniques of RELAXATION.They are Yoganidra, Jacobsons Progressive Muscular Relaxation, Schultz Autogenic Training, Relaxation Response, Bio-feedback and the latest being Guided Psycho-Somatic Relaxation.

- Details

- Hits: 4091

Deconstructive Contemplation -- A Contemporary Psycho-spiritual Discipline

© Peter Fenner, Ph.D

I would like to thank Prof. Barry Reed for suggestions which have improved the accessibility of this paper.

- Introduction

- Prerequisites

- Fixation

- Deconstruction

- Disclosing the Self-Referentiality of Beliefs

- Obvious And Transparent Beliefs

- The Juxtaposition Of Opposite Beliefs

- Creating A Clear Disclosive Space

- Guiding Observations

- Awareness And Action

- Somatic Sensitivity

- Facilitation

- A Course Format

- Deconstructing A Course

- No Best Practice

- Deconstructing The Notions Of Engagement And Disengagement

- Deconstructing The Phenomenon Of Fixation

- Deconstructing Deconstructive Contemplation

- References

Deconstructive contemplation is a contemporary expression of the liberating, analytical insight contained in the Perfect Wisdom (Prajnaparamita), Middle Way (Madhyamaka), Contemplative (Zen), and Complete Fulfillment (Dzogchen) traditions of Buddhism. It is a practical discipline for the disclosure of beliefs that structure our experience of reality, as these beliefs are manifesting. It makes apparent the transparent assumptions and embedded beliefs that shape our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions. In the process of revealing our belief systems, deconstructive contemplation discloses the fixations that freeze and solidify our experience of ourselves, and the world by interpreting the world and ourselves through dualistic categories. By solidifying our thinking, these fixations support serious and inflexible opinions about how things are. They lock us into habitual ways of living life and interpreting the world, and reduce our repertoire of healthy and sensitive emotional responses.

The principal assumption of deconstructive contemplation is that reality is created through our beliefs (prajnapti-sat). This assumption allows us to see the constructed nature of our experience. This is an assumption which is itself deconstructed within this work - leaving "reality-as-it-is". So in the final analysis deconstructive contemplation is a "non-event". As the Perfect Wisdom (Prajnaparamita) tradition of Buddhism says, it is a radical teaching that is openly presented as a non-teaching. However, for as long as we figure that there is something we need to do, deconstructive contemplation fits the bill, for some at least, as a sophisticated tool for recovering that which we can neither gain nor lose.

The use of the term "contemplation", in the term "deconstructive contemplation", points to the fact that the practice of deconstruction occurs most fluidly and naturally within a psychological space that is free from urgent or intense emotional reactions. This work supports, and is supported by, a mellow and psychologically mature personality structure that isn't heavily fixated or opinionated. Contemplation in this context does not refer to a practice, such as formal meditation, which is segmented out from the rest of our everyday activities. Thus, deconstructive contemplation cannot be compared with a methodology such as Theravada-based insight meditation (vipashyana).

The minimum prerequisites for this type of work are a spiritually mature, attuned intelligence and the absence of intense and overpowering emotions. By and large, this perspective can't be cultivated when people are in an emotional crisis. In such circumstances, people are often locked into the validity of their experience to such an extent that they can't begin to activate the critical intellect required to dismantle their interpretation of their situation. Also, if people are urgently trying to relieve intense emotions they are usually seeking explicit suggestions and methodologies, both of which are lacking in this work. For such people, this work would be frustrating and pointless. Also, if people are experiencing intense emotional pain, the need to urgently escape their suffering can propel an ungrounded participation in this work. They could use this work to "dis-connect" from their pain, instead of disclosing its constructed nature.

This work also requires an open mind and critical intellect. In particular, people need to be able to track their thinking in a gentle yet precise way over an extended period of time in order to appreciate the underlying beliefs that mold their lives. The type of intelligence required is quite distinct from that which is used in developing elaborate theories, or trying to prove the validity of some particular interpretation of spirituality. This work is inaccessible to people who are only looking to defend their own ideas.

Fixation occurs every time we take a rigid and inflexible position about any aspect of our experience. When we are fixated, we invest mental, emotional, and physical energy in defending or rejecting a particular interpretation of reality. All forms of fixation can be traced to a core assessment that something is missing in our lives. What is missing can be anything from a nice cup of tea through to enlightenment. We feel that "This isn't it" - where IT represents our particular version of how things should be. We are sure that something is happening that shouldn't be happening, or that something that should be happening, isn't. Either view is a fixation which throws us into emotional confusion as we struggle to gain whatever IT is. We fear not getting IT, and having got it, we fear losing it. And by all counts IT will probably be derived from our concept of a state of enlightenment, i.e., a state of limitless possibilities and unending happiness.

The base-line assessment that "something is missing" is cyclically displaced by the feeling that "This is it". For a time we validate that things are turning out as we would wish. We figure that we are getting it, or have got it - this is how things should be. We might even convince ourselves that we have arrived at the long sought after goal of our spiritual endeavors. However, the belief that we have got it sets up the possibility of losing it, as we reconstruct that we don't have enough of it, and that we could use more of it. We also question if this really is IT and even if it is, whether we now want it.

The core assessments that "this is it" and "this isn't it" spawn innumerable secondary fixations. In terms of our personal and spiritual development we spend a huge amount of time and energy constructing the interpretations that we are making progress or that we are standing still. As these constructions shift and change we spend yet more time trying to work out whether we are stuck or mobile. We oscillate between trying harder and giving up. We determine that we do or don't need help, or find ourselves unable to decide whether to seek help or go it alone. Sometimes we are clear and committed and at other times we are confused and vague, struggling to determine whether our experiences are meaningful or meaningless, real or unreal.

These experiences are palpably real when we are in the middle of them because they are supported by complex "stories" that validate our core assessment. For example, if we assess that we aren't making progress in our spiritual pursuits we listen to a battery of "supporting evidence". We judge that we should be calmer, more aware, or less reliant on foundational methodologies. We draw on the claims of others - who are making progress - and conclude that there is insufficient payoff for our sincere effort. These fixations lock us into habitual and conditioned ways of living life and interpreting the world. They throw us between the extremes of elation and depression, excitement and resignation.

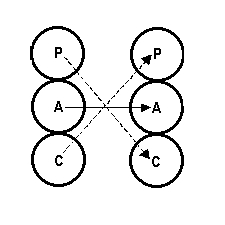

These fixations emerge in an attempt to produce a fixed and solid experience of ourselves and of the world. Two opposite viewpoints or beliefs emerge in dependence on each other - coexisting, separating and finally dis-connecting. When they have dis-connected the two beliefs appear to be independent of each other. Our attachment to one as valid and the other as invalid produces a fixation.

Our fixation with a particular personality structure (pudgala) emerges in the same way. Firstly we develop the distinction "self", or me, by contrasting this with what we are not. This provides a platform for developing a specific identity. Through time we build up a set of beliefs about ourselves. If we identify with being sincere we simultaneously dis-connect and dis-identify with being insincere. If we think of ourselves as unreliable we dis-identify with being reliable. We acquire all our beliefs about who we are in this way. We then spend the rest of our lives defending, avoiding, or trying to change our identity.

Deconstructive contemplation is a gentle procedure for neatly dissolving fixations by revealing that our everyday and professionally-informed interpretations of reality are self-referencing mechanisms for deceptively validating the core fixations that "This is it" and "This isn't it." By disclosing the beliefs that internally validate our fixations, these fixations lose their capacity to control our experience. By revealing their core structure in real-time, we discover that our fixations are arbitrary and that they don't refer to a solid, objective reality. Ultimately we discover that our fixations aren't fixations. We see that a fixation is merely a concept that is superimposed on the flux of our experience. In this way deconstructive contemplation discloses the open and fluid texture of reality (shunyata).

As a procedure for disclosing fixations, deconstructive contemplation is loosely based on the Middle Way (Madhyamaka) tradition of Buddhism. In its traditional Indian and Tibetan settings Middle Way deconstruction systematically demolishes fixed beliefs through rigorous logical investigation. The Tibetan instructional manuals on deconstructive contemplation outline a variety of methods which are tailored to different types of fixed beliefs (drshti). These methods are employed in a rather mechanical way during formal sessions of meditation. A meditator will fabricate a particular fixation, perhaps by recalling a past situation in which the fixation was active. The belief that supports this fixation is then processed using strict logical procedures designed to progressively dismantle the fixed belief through disclosing internal contradictions (prasanga).

Contemporary deconstructive contemplation differs from traditional Middle Way methods in two important ways. Firstly, it operates in a way that transcends the need for formal periods of meditation. In fact, contemporary deconstructive contemplation systematically deconstructs the activity of meditation, whenever meditative activity becomes a self-justifying method for blindly conditioning beliefs in our personal worth and spiritual progress. In this regard deconstructive contemplation is closer to the original Perfect Wisdom (Prajnaparamita) tradition. A second difference is that deconstructive contemplation focusses on dismantling fixations as and when they arise rather than artificially reactivating pre-existing fixations in the context of meditation. These differences make deconstructive contemplation much more organic and fluid when compared to traditional, stylized methods for meditating on egolessness (nairatmya). Rather than being driven by hard-nosed logical analysis, the deconstruction of fixations occurs naturally, as a consequence of the creation of a clear, disclosive space.

Disclosing the Self -Referentiality Of Beliefs

In general terms, deconstructive contemplation moves gently through two or three different phases. In a practical context these phases are only discernible to a skilled observer as each one blends fluidly into the next.

Deconstruction begins by disclosing the "stories" that internally validate our beliefs at any point in time. The stories within which our beliefs are embedded are uncovered as self-referencing systems of meaning that render our assessments true and factual to us. These stories contain an internal logic in just the same way that the interpretation we are developing here has its own localized coherence. These self-referencing stories gain their plausibility from various forms of "evidence". Typically they draw on memories, causal explanations, and authoritative sources, such as friends, mentors and psycho-spiritual literature. For example, if we are locked inside a belief that we need to engage in a certain spiritual practice (such as meditation), this belief will be linked to judgements that it has helped us in the past, anecdotal support from a network of practitioners, reference to a "lineage" of transmission, and declarative claims in texts that advocate our chosen methodology.

Deconstructive contemplation uncovers these explanations and allows us to see that the validity of our core assessments depends on the interpretation (or story) within which they are embedded. We see that under a different interpretation the core assessment would be false or indeterminant. For example, the belief that we need to engage in a spiritual practice is rendered invalid when held in conjunction with a belief that spiritual activity merely conditions, and perpetuates a sense of incompleteness.

The process of disclosing the local or contextual validity of our beliefs doesn't involve heavy intellectual analysis of how we think and feel. Instead, it is a function of creating a clear disclosive space that allows personal and social discources to be naturally revealed. When delivering this work in a course format, facilitators work with participants to disclose what is already there through simple exercises, group discussions and one-on-one conversations. This pro-active disclosure of core fixations distinguishes this work from other processes such as the Therav›da-based insight meditation (vipashyana) that is widely taught in North America and Europe.

In this phase of the work, people begin to recognize that any opinion or viewpoint that they are inclined to defend or reject signifies a fixation. They become sensitive to the energy modulations that are triggered when their interpretations of the spiritual endeavor are supported, or challenged, by their present experience. They become gently aware of the feelings of comfort and confidence that arise when they judge that they are on-track, and the feelings of frustration, threat and disappointment that occur when they think that something is wrong or "shouldn't be happening." People begin to appreciate that these feelings and emotions are indicators of obvious and subtle forms of fixation. This awareness produces a natural adjustment so that people no longer feel compelled to vigorously defend their beliefs. People see that their beliefs are the product of prior experiences or conditions, and they are therefore content to let their beliefs and opinions arise as thought forms that don't need to be cultivated or suppressed. No special instruction or directive is needed to produce a less defensive or less confrontational relationship with our own and others' beliefs. A more mellow and spacious mood emerges as a natural consequence of seeing the interdependent relationships within our beliefs, and between our beliefs and feelings.

Throughout this process we focus on disclosing and deconstructing fixations as they manifest. This is what distinguishes the practical from the theoretical application of deconstructive contemplation. Thus, whilst some transpersonal patterns of fixation may be deconstructed in a group setting the focus is always on locating and dismantling live fixations.

You can gain a sense of this by speculating right now about the beliefs that account for what you are presently doing. Very likely, the act of reading this paper discloses a belief that there may be some benefit or gain in studying the (as yet ill-specified or unknown) discipline of deconstructive contemplation. Reading this paper can disclose the active presence of a belief that something is missing at a personal and/or professional level, and that you can recover, or discover, what is missing by reading or listening to what others might have to say. This belief, in turn, discloses a belief that you can become more competent, skilled or insightful in managing your own and others' lives. This in turn points to the belief that insight or competence is "something", and that you can learn it or acquire it. At the very least you are engaged with this paper through a need for stimulation or entertainment.

Were we to unpack these beliefs and see how they only hold up within a complex, personally-customized story about how we should be able to do things we can't, we would begin to deconstruct the belief that something is missing. We would discover, for example, that our needs are based on assessments about what we should have, but don't have. And to the extent that the story within which these assessments are embedded is convincing - to the degree to which we really believe our interpretation - we will experience the desire to aquire that which we don't have.

In a course context we do not need to unravel these "stories" in a laborious way. Rather, we present generic versions of these stories in group meetings. In essence these stories are simple because they disclose the most basic structures of the psycho-spiritual enterprise. We explain, for example, how we can invalidate our experience by constructing an interpretation that we shouldn't be experiencing whatever is happening. Participants share how they may have been constructing such an interpretation. If someone has been seduced by a tantalizing description of "bliss and enlightenment" they may share the impact of this expectation on what they are presently experiencing. If people begin to really like what is happening, or experience supposed "breakthroughs", we use this as an opportunity to disclose how we validate our experience through reference to a story about what should be happening to us. The structures that are disclosed reflect the fixations that manifest at any particular time. Participants reflect on their personalized versions of the generic constructs in the periods between group meetings. Participants aren't instructed to do this. It is a natural outcome of the intentionality and energy that is created and focussed during group dialogs.

Obvious and Transparent Beliefs

In the initial stages of this work the extent of deconstruction that occurs matches people's willingness to share the beliefs they access at an obvious and familiar level. They become aware of beliefs that have been cultivated through their own unique exposure to culture and education. In Buddhism these are called acquired (parikalpita) beliefs. Given the psycho-spiritual nature of this work, people tune in to their own personal discourses about psychological and spiritual development. They speak as though they "know" where they are, and where they would like to be. They also tend to have reasonably firm ideas about how to get there. Within a course structure people quickly appreciate how their beliefs derive from traditions, teachers, books, etc. They also appreciate that there are alternative and equally authoritative discourses, some of which directly contradict their own. Through sharing in a psychological space that neither supports nor rejects any particular belief system, people begin to see through their beliefs in the sense that they no longer need to defend or reject what they are thinking. People become present to their thoughts in a simple and uncomplicated way.

Behind our acquired belief systems are structures that shape our experience of ourselves and of the world at a more foundational level. These structures show up in the basic constancies and recurrent patterns in our lives. They shape the very landscape of our experience. Generally we don't observe these structures because they function in a more obvious way. In Buddhism these transparent structures are called innate (sahaja) beliefs. In contrast to parikalpita beliefs, we are born into these deeper structures. In fact birth is one of them. The closeness and familiarity of these structures makes them invisible. Also our capacity to observe them tends to be displaced by the density and urgency of our thinking, and the complexity of our interpersonal activities. However, once people can appreciate their acquired beliefs (parikalpita) without needing to apologize for them or take them seriously, they automatically begin to observe their more transparent belief structures.

The first structures to emerge often reflect people's need to know what is happening. They begin to see how they construct the phenomenon of progressing towards a goal. The course becomes a microcosmic expression of people's need to be able to track their progress towards some privately designed goal. People experience moods of expectation and frustration that can accompany the "path of waiting". They experience how the "path of waiting" is built on the belief that "IT isn't happening now" and see how this motivates them to discover what they need to do to make IT happen. Participants experience how waiting is displaced by "arriving", i.e., getting IT, and how arriving is displaced in turn by more waiting, as people reconstruct that they have lost IT.

People see how they cycle between experiences of success and failure as they judge their progress, or lack of progress, against a quite complex set of assessments about what they have done, whether their past training is a help or hindrance, what there is to "get", whether they are getting it, if there is anything to get at all, who is to judge success and failure - themselves, a facilitator, other participants, etc. The disclosure of these structures is not specifically intellectual. People experience these structures together with the moods and emotions that accompany them. They experience the feelings of frustration and disappointment that are fused with the assessment that they have failed. And they get high on the feelings of excitement and elation that accompany judgements of success. These feelings are experienced as they are in other situations. However, rather than simply enjoying or enduring these feelings, people see how they are conditioned by the stories they weave about what should and shouldn't be happening to them.

Other transparent structures that this work reveals include the construction of authorities, or sources of knowledge in the form of people and traditions, and the creation of dependency relationships with authorities. By revealing the personal and societal discourses that support these structures, people begin to operate outside an identity of needing or giving help. In a relatively short space of time people are accessing the deeper flows of conceptuality that reveal their sense of uniqueness and separation from the world.

As people progressively disclose and deconstruct their deeper beliefs, they encounter their identity at a more basic or existential level. They experience the sense of just wanting to hang onto something familiar, or wanting to escape the experience of being who they are. They also discover the beliefs that produce the transpersonal features of our experience such as time, motion, location, and distance.

The Juxtaposition of Opposite Beliefs

Our usual pattern is to cycle between conflicting fixations. We oscillate between feeling separate and connected, clear and confused, fulfilled and lacking. We need help at one point and then don't need it some time later. We get locked into perservering, striving to determine the "right" perspective, which then gives way to giving up. However, when we see that these are responses to the conflicting constructions that "this isn't it" and "this is it", the oscillations flatten out and we move into a space where these constructs lose their capacity to describe an objective or subjective reality. For example, when we see ourselves move through a number of cycles of waiting and arriving with no apparent change in terms of real movement towards a solid goal, we see how our concepts and beliefs create the phenomenon of progress against a highly fluid and vaporous concept of what it is that we ultimately want.

We see how we can interpret our experience differently, even without changing our thinking, feelings, or physical circumstances. For example, instead of believing that we are stuck and just aren't getting IT, we can just as legitimately construct that we are free and mobile. This insight releases our attachment to a limiting interpretation of our circumstances. Having seen how we can simultaneously construct the two experiences of constriction and freedom, we realize that there is no such thing as being really bound or really free.

Two opposing perceptions are juxtaposed over the same moment of illumination. For example, if we are participating in a course, we simultaneously experience the possibilities that we are participating and not participating. We see that whether we are participating or not is purely a matter of what we think we are doing at any point in time. The space itself neither confirms, nor denies, either belief. There is nothing within the course that we can refer to in order to determine if we are participating, or not participating. The capacity for two opposite interpretations to equally describe where we are, renders such assessments meaningless. The juxtaposition of these perceptions deconstructs the beliefs that we are either "doing it" or not "doing it". This same type of insight occurs around "getting it" and "not getting it", making and not making progress, needing and not needing help, being confused and being clear. In terms of their identity people experience how a sense of separateness intimately connects us with the world, and how a sense of connection confirms our uniqueness. Furthermore, to the extent that this work is construed as a vehicle for gaining spiritual insight or liberation, we see that there is no difference between reality and illusion, wisdom and ignorance, bondage and liberation. At this point the need to make such distinctions simply doesn't compute.

As an example of the transitions that occur: when people first share what they think is happening during a course, they might give an interpretation based on a comparison with other work they have done. At a later point they might begin to struggle with not being able to readily make sense of what is happening. They begin to question whether they know what is happening. At this point they reach a deeper level of belief. They may begin to connect with the belief that they need to understand their experience. This point can evolve further to a place in which they don't know whether or not they know what is happening. Participants can arrive at a point where the assessments "I know" and "I don't know what is happening" can equally apply.

As the interdependence and groundlessness of people's fixed beliefs is revealed, fixations begin to dissolve naturally. This produces pockets of clarity and openness. The energy for constructing bondage and release is liberated into a state that is free from bias and limitation. As this work evolves, the process of releasing fixations becomes more natural and effortless. The heaviness and density of people's conflicting emotions thin out, producing greater spaciousness and ease. Through this process people can experience a delightful space that is free from reactive emotions and habitual interpretations. They transcend any preoccupation with getting it or losing it. And in saying this, I acknowledge that you might think this is an experience worth gaining, or avoiding!!

Creating a Clear Disclosure Space

In general there are two ways to stimulate the observation of fixation. One way is to impose a rigorous level of structure and constancy over one's physical activity. This way fixation breaks out in an attempt by the ego to affirm its own uniqueness and independence against a background of discipline that is imposed from outside. Zen Buddhism tends to choose this way for stimulating and working with ego fixation. An alternative way to observe fixations is to remove structure and meaning so that there is no reason for doing or not doing what we are doing, nor any way of determining whether we are on–or off–track, in terms of our spiritual aspirations. In this situation we search for grounding and reference where there isn't any, by creating our own systems of meaning, in order to have a purpose and to track our performance and progress. This allows us to observe habitual patterns of fixation.

We have found the later method particularly effective for disclosing both obvious and subtle forms of spiritual and psychological fixation. Thus, our work occurs in a space that is created by the progressive removal of specific and generic structures and assumptions. The removal of such structures and assumptions allows people to see how their experience is constructed. For example, there are no practices or conversations in this work which specifically allow people to conclude that the course has, or hasn't, a purpose. The creation of such a space gives people a unique opportunity to see how they need to construct meaning, purpose, and outcomes. It brings their constructions into high profile because the "space" doesn't collude with these constructions. People discover what they, and they alone, make out of the space. Also, because the space neither validates, nor invalidates people's constructions, it isn't skewed towards any particular personality profile. For example, it isn't biased towards encouraging conceptualization and suppressing emotions, or vice versa. The environment allows participants to experience the structure and behavior of their personality without distortion. Consequently, everything that is created during the course is an accurate reflection of what occurs away from the course. The belief that "something is missing or wrong" emerges in the same way as it does in other situations in life.

The creation of the space is very much a function of the facilitators' capacity to not condition the space with their own beliefs about what should and shouldn't be happening. In fact, the evolution (and effectiveness) of this work is driven by the progressive disclosure and removal of assumptions and expectations that facilitators have unwittingly imported into the space. Facilitators also need to progressively dismantle any imputation of direction, meaning, or lack of meaning that has been inferred from the light structure and content that initially defines the working space.

Whilst the structure of deconstructive conversations is loosely modelled after Middle Way "unfindability" analyses, the ambience for undertaking this work is inspired by the Complete Fulfillment (Tib. Dzogchen) and Complete Seal (Skt. Mahamudra) traditions of Buddhism. These traditions advocate a transcendental balancing of our thinking, feeling, and acting, in preparation for the liberating insight that deconstructs the differences between application and non-application, bondage and liberation, etc. The integration of these extreme orientations is achieved through a natural correction that occurs by observing their manifestation.

The great fourteenth century Tibetan master Longchenpa summarizes the most important Complete Fulfillment principles when he writes:

If there (are views and opinions) to be negated and established, and (experiences) to be rejected and accepted, then in the process of doing this you get caught in a web of dualistic fixations (based on) hope and fear. Because we have gone astray and haven't reached our desired destination, the point is to cultivate the non-rejection and nonacceptance of whatever arises.

At a cognitive level one progressively filters out any tendency to validate or invalidate one's own and others' beliefs systems. Similarly, one checks and corrects the tendency to view one's experience as expanded or contracted, sublime or mundane. At an emotional level one learns to operate in a way that filters out the extremes of depression and excitement. In summary, one acts to progressively remove all cognitive and emotional bias from one's experience. While these directives are given prominence in the Complete Fulfillment tradition, a related set of parameters occurs in the original teachings of Buddhism which recommends that we avoid being driven by the eight worldly aspirations; namely, loss and gain, pain and pleasure, fame and disrepute, praise and denigration.

In our own work we have enriched the above principles by offering a more comprehensive account of the biases that inhibit the dismantling of our fixations. When we describe these biases we do so in a relatively casual and common-sense way, using language that accords with our everyday way of thinking and talking about them. This helps to transform theoretical and attractive-sounding suggestions into instruments for the direct and real-time disclosure of cognitive biases and emotional fixations. By describing the personalized discourses and feelings that accompany generic fixations, we can easily track their structure and manifestation as they occur. The following list summarizes the type of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral biases that are incrementally articulated in establishing the personal and social atmosphere that invites people to inquire into the reality of their "breakdowns" and "breakthroughs". In the context of this work people are invited to observe in real-time how they are:

• drawing attention to themselves, or diverting attention from themselves.

• exposing themselves to, or shielding themselves from, fears and

perceived threats.

• helping or hindering their own and other's process.

• making things easy, or difficult, by "cruising" or "busting their guts".

• trying to please, or aggravate people.

• clamming up, or speaking out.

• letting it all out (i.e., being an open book) or cultivating an aura of

mystery around themselves.

• holding back, or pushing forward.

• trying to contract, or expand, their field of influence.

• pushing on, or giving up.

• trying to intensify, or dilute their experience.

• dramatizing or trivializing a breakdown or breakthrough.

• attempting to prolong, or shorten, what they are experiencing.

• resisting, or giving into, an experience.

• validating or invalidating their own and other's beliefs.

• attacking and defending beliefs, or acquiescing to others' opinions.

• agreeing or disagreeing with what others are saying or doing.

• expressing interest, or disinterest, in other peoples' thoughts and

conversations.

• approving or disapproving of how they and others are being.

These and other biases manifest uniquely for each individual. For example, what constitutes speaking up for one person may represent relative silence for another.

In this work, facilitators offer their observations on how these biases are manifesting. Whilst facilitators are rigorous in providing feedback to participants, they do this in a way that is neither heavy handed nor intrusive. Facilitators also function as role models, as they personally implement these principles.

People also observe how they can engage in this work half-heartedly or make hard work of the process. Furthermore, to the extent that we distinguish actions from awareness, people can interpret this activity as either the mere observation of biases or their elimination from their experience. These biases reflect a passive and active approach to spiritual work, respectively. By observing such tendencies, and acting in terms of these observations, they move into a space where they are neither compensating for a bias nor resisting the impulse to make a correction. In this way balance is applied to the relationship between observing and correcting these biases. The result is that people neither actively intervene to change their thinking and behavior, nor remain merely inert observers of their biases.

An awareness of these biases produces a serene and alert atmosphere that is conducive to the more rigorously deconstructive dimensions of this work. The gentle observation of biases slows down people's thinking and introduces a smooth pace into their physical activities. Their personalities become integrated and harmonized and they achieve a sense of emotional balance and physical well-being.

At an interpersonal level an awareness of these biases produces a delightful atmosphere in which there is a harmonious balance between privacy and sharing. People neither intrude into other's space nor convey the message that they don't want others to come near. People neither operate in an insensitive manner nor feel the need to tread warily People are respectful without being obsequious.

Facilitators also sensitize people to the somatic effects of fixation. People learn to use their bodies as instruments for detecting the presence of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral biases. They become sensitive to the bodily sensations that signal they are operating from a reactive space. They begin to feel how they are physically drawn into some situations and repelled by others. As this awareness grows, feelings of attraction no longer magnetically grip their body, and feelings of aversion no longer repel. An uncalculated correction occurs, such that they are no longer compelled to move into attractive situations, nor to avoid distasteful ones.

People give relatively less energy to their strategic intellect and begin to operate more from a feeling dimension. At any point in time, the spatial location of their body represents a point of emotional equilibrium in that it precludes the triggering of intense desire or aversion in response to the environment. Similarly, the movement of their body is defined by a path wherein they are neither giving into nor resisting their desires. They move into a highly responsive feeling state which is empty of coarse feelings. People's capacity to experience their own and others' energy increases as specific feelings dissolve into a heightened state of sensitivity.

The facilitation of this work brings forth its own expression of these principles. Firstly, we neither encourage nor discourage people's participation in this work. Were we to encourage people's participation we would contribute to stimulating expectations that would then need to be deconstructed once they were involved in this work. In fact, if people can't wait to participate in this work we tend to cool right off in communicating it to them. But, nor do we discourage people's interest and involvement because in the absence of this, or related work, people just continue to live out their painful constructions.

Once people are engaged in this work, we neither positively nor negatively reinforce their own assessments about making, or failing to make progress. We listen to any assessment people may share with us, but we do not buy the assessment as a description of an unconstructed reality. This involves listening in a way that neither validates nor invalidates people's interpretation of their present situation. One needs to be able to listen closely and attentively to people's constructions without this triggering any feeling in participants that one is accepting or rejecting, what they are saying. Of course, one's capacity to listen from a space that is neither earnest nor dismissive depends on being able to see through one's own constructions.

Furthermore, in this work, facilitators neither make themselves excessively

available nor unavailable to participants. They neither encourage people to

communicate with them, nor put them off. Facilitators don't collude with participants' needs to dissipate the rigor of this work by encouraging trivial conversations. But, nor do they force participants to sit with their painful constructions, building them up in their minds to the point where they lose the clarity and peace that is necessary to see through their constructions. Consequently, the timing of conversations ensures that they are consistently deconstructive in nature.

A skillful balance between accessibility and inaccessibility ensures that participants neither contrive to put themselves on the level as facilitators, nor project "guru-type" identities onto them. Facilitators support this space by neither putting themselves up, nor putting themselves down. They aim at neither accepting nor rejecting the identities that participants project onto them. Ideally, they are neither interested in gaining people's approval nor avoiding their wrath.

In summary, we could say that facilitators do not try to make things easy or difficult for participants. By neither helping (making things easy) nor hindering (making things difficult), they free participants from the compulsion to seek or resist help. The space this produces cultivates a balance between dependence and independence.

This work is currently offered in courses that range from one to six days. The course format exists because many people believe that the opportunities for spiritual growth and development are enhanced by setting aside specific time and intensively engaging in activities that differ from those we perform during our ordinary working and family lives. This is the reason why workshops, intensives, and retreats are popular structures for transformational work.

A "course", by its very nature, also speaks to our need to be able to "progress" towards whatever it is that we are seeking. By virtue of having a beginning, a middle, and an end, a course initially supports our need to track our progress towards completion - be this construed as achieving a rarefied spiritual goal, or getting in touch with our present experience. The feedback that is provided in a typical course also allows us to distinguish our location in terms of being closer to, or further away from, the result that we seek. Generally, courses also offer the promise of achievement, and provide the incentive of positive feedback and reinforcement as we progress towards, and finally celebrate, achieving a mutually agreed upon goal. A course structure also expresses and supports the belief that there is something specific that we should be doing. It allows us to believe that there is a "correct' or 'best" thing to be doing.

These "expected" features of the course format mirror the structure of spiritual paths leading towards a goal of freedom or liberation. As such, a course can easily function as a microcosmic expression of the psycho-spiritual endeavor. The course format is thus a logical interface for this work because it can be used to stimulate an expression of the very beliefs that define people's psycho-spiritual activities.

Whilst the expected and generic features of courses do attract people to this work, our own course systematically deconstructs the concept of a "course" by disclosing the beliefs that validate this structure as a vehicle for the delivery of this work. When people project that the course is a suitable event for realizing their goals and aspirations we disclose the beliefs that fuel this projection. We begin the disclosure of these beliefs prior to people's participation in a course (as we are doing now), and during the course itself.

For example, if someone asks whether the course will help them, we point out that the course is not designed to help them. However, it will allow them to see how they construct and deconstruct the identity of "needing help". If they think that this sounds like a very valuable insight to acquire we point out how they are constructing a desirable outcome, possibly in order to validate their participation. If, as can sometimes happen, people flip to an opposite fixation and figure that the course is pointless if it can't help them, we simply point out that the level of disclosure we bring forth rarely occurs outside of this course. Still, we do not condition a belief that participation in a course is necessary for engaging in this type of work.

During the course itself we strike a balance between too much and too little structure. We generally reject a complete absence of structure because this can stimulate a level of anxiety that reduces people's capacity to neatly disclose their fixations. On the other hand, the imposition of a heavy and rigid structure simply feeds into people's belief that they need to be doing something definite and concrete in order to achieve a desirable outcome. Thus, at least initially, we produce a gentle misalignment between the course and people's expectations. Too much misalignment makes people too uncomfortable and too much alignment makes them feel so comfortable that there is no stimulus for exploring belief systems. You could say that the level of structure in the course is continuously assessed and adjusted so that people are neither comfortable nor uncomfortable.

If people are seeking more structure, the structure naturally retracts. Less is provided for people to work with (i.e., hang onto). If participants are drifting off or getting totally lost in the absence of structure, some structure re-emerges. In this way the course automatically acts to correct people's fixation with structure. As the ninth century Chinese master Linji says about Zen: "If you try to grasp Zen in movement, it goes into stillness. If you try to grasp Zen in stillness, it goes into movement... The Zen master, who does not depend on anything, makes deliberate use of both movement and stillness."

If and when processes or exercises are introduced in this work, we explain how their introduction is a reflection of people's need to engage in definable processes in order to take them to a place that is more preferable than where they feel they are. In other words, we point out how people begin to look for a method when they want to displace the belief that "something is missing". This serves to ameliorate people's need to do an exercise. However, if they then think there is no need to do the exercises that are offered, we observe that they must be thinking that "not doing" is the best thing to be doing. In this way people's participation or lack of participation in specific exercises, constantly reveals their strategies for "getting IT", or "keeping IT", if they think that they have already got it.

The experiences of progress and lack of progress are deconstructed in part by the absence of specific signposts against which people can assess either movement or its absence. The notion of a beginning, middle, and end

dissolves because there is no structure within this work that corresponds to "getting it" or "not getting it." The experience of progress and lack of progress are also deconstructed through an absence of positive and negative feedback. When participants attempt to co-create success or failure, i.e., enrol a facilitator in an interpretation of their participation, facilitators will give simple feedback that they are seeking approval (i.e., confirmation) or disapproval (i.e., non-confirmation) of their experience.

Facilitators simply act as mirrors to disclose people's beliefs without accepting or rejecting what they say. If participants assess that they are making progress we might ask "Progress towards what?" If they respond by saying, "Becoming more aware," we might say "Why are you trying to become more aware?" If they say, "Isn't that what this work is about," we might respond by saying "What have we said that gives you that idea?" In this way they learn to see how they construct both a goal and a method for achieving their goal. If participants construct that they "aren't getting it" - that they are failing the course, we might ask: "What is it that you think you could, or should, be getting?" If they say, "Well I'm not feeling blissful," we might respond, "Is that what you think the course is about," in a way that will let them see that this is their own construction of the space.

The deconstruction of progress and lack of progress also means that there is no such thing as "finishing the course". There simply isn't any benchmark against which people can assess their level of completion, or lack of completion. Toward the end of the course participants are invited to consider what could constitute, or signal the end of the course. It becomes clear that "saying goodbye", "getting into one's car", "leaving the venue", "arriving home, etc. are simply the next things that they will be experiencing. Further, because there is no issue around having completed it, there is no concern about losing it either. If people begin to anticipate losing it, we reactivate the space by asking them WHAT it is that they think they have acquired, that they could lose.

When people construct a purpose for their participation in any program or process, they necessarily assess their participation against a set of alternatives for realizing their goals. They begin searching for the best thing to be doing. Within a course setting people can spend a considerable amount of time speculating about the most useful or fruitful activity to engage in. They will become preoccupied with assessing the relative value of what they are presently doing against other possibilities. People can swing back and forth between the extremes of thinking that they are completely on-track (i.e., that they are clearly doing the best thing possible) and thinking that they are totally off-track and wasting their time.

Of course, given the minimalist nature of this work, people can also construct that it has no purpose, but this doesn't relieve them of the search for a "best practice" either. The idea of "no purpose" can be understood in two different ways depending on whether people are validating or invalidating this work. If people are within a mind-set that validates this work they can conclude that the purpose of the course is that it has no purpose. This leads them to experiment with how best to "get" that it has no intrinsic purpose. For example, should they try to be natural and unconcerned about striving for a goal? Should they try to become more aware of their feelings? Should they try to be evenly aware of everything? Should they deconstruct the discourse of "having a purpose"? Should they deconstruct the discourse of "not having a purpose"? Should they try to do nothing? Or, should they not try to do nothing?

People can also conclude that the course is pointless, by virtue of having decided that it won't produce the results they are seeking. In other words, they invalidate the course as a vehicle for realizing their goals. However, having negated the course (i.e., made it the worst, or at least a negative thing to be doing), they are simply looking for the "best thing to do", outside the course setting. So, whether people construct that this work is useful or useless, they are still caught in the idea that there is a "best thing to be doing".

An awareness of these limiting discourses arises as a natural consequence of the very minimal and flexible structure of the course, and from the fact that facilitators neither validate nor invalidate any particular activity. From time to time, we might also invite participants to inquire into the question of "What is the best thing to be doing?" For example, if someone is engrossed in the idea that there is a best thing to be doing, we might invite them to change whatever it is that they are doing so that it is fully aligned with their idea of the "best thing to be doing", and then observe what happens. Typically there will be a short-term experience of being on-track which is gradually displaced by the belief that there is now something better for them to be doing. After observing this repeating pattern, they will be primed to more rigorously inquire into the very notion of a "best activity".

They will readily appreciate that the best thing to be doing is either the activity they are presently engaged in, or something else. We then unpack both alternatives. If the best thing to be doing differs from what we are doing we cannot do it, because it is displaced by what we are presently doing. Alternatively, if the "best thing" to be doing refers to a future activity, then the "best thing to be doing" is simply thinking about an alternative and better thing to do some time later on. Thus, the idea of a "best practice" is constituted as a speculative discourse about what may be a useful thing to do in the future. In fact, there are times when people's present practice mainly consists of wondering about what better thing they could be doing. If people think they should be doing this better (and alternative) activity right now, they come to appreciate that they are simply constructing that they should be doing something that they aren't!

At this point people can be tempted to conclude that the best activity must be the one they are doing, since this is the only thing they can be doing. This implies, once again, that they could be doing a less useful or less constructive action which they can't be doing if they are doing what they are doing. Given that they can't be doing anything else, they see that it doesn't make sense to call it best or worst.

So, the best thing to be doing is never something that people can be doing now, unless it consists of either thinking that one should be doing what one isn't, or speculating about what one could or will do in the future.

Deconstructing the Notions Of Engagement And Disengagement

Deconstructing the idea of a "best practice" naturally leads to dismantling the distinction between engaging, and not engaging in this work. This particular dimension of deconstructive contemplation is aligned with the dissolution of the division between meditation and non-meditation that occurs in the Complete Fulfillment (Dzogchen) and Complete Seal (Mahamudra) traditions. On the one hand, these traditions reject the heavy handedness of forced meditation, and on the other, they reject the extreme (and now somewhat popular) interpretation of spirituality which suggests that there is nothing to do, other than what we are doing. The texts of these traditions distinguish a state that is neither static (gnas) nor dynamic ('phro), and which isn't conditioned by either the peace of deep meditative equipoise, or the turbulence of everyday activities. For example, Longchenpa declares that there is no real activity of meditating (sgom) as distinct from not meditating. And the powerful Indian practitioner, Shavari, says that the "perfect meditation is to remain inseparable from the state of non-meditation."

Deconstructive contemplation duplicates the dissolution of the distinction between "doing" and "not doing". However, rather than point to a way of being that transcends the fixations of practicing or not practicing, deconstructive contemplation critically dismantles the distinction.

The very minimal assumptions of this work, and the fact that all structure is revealed as a reflection of people's need to be doing something, allows us to ask participants what they are doing, and why they are doing it. We might, for example, ask people, "What is it that you think you are doing that is consistent with the assumptions of the course?" Their response will disclose their particular "take" on what constitutes participating. They might say that they are "simply being aware of whatever they experience." To which we might respond, "Give me an example of not being aware of what you are experiencing?" People see the tautological nature of their claim. They see that the claim to be aware of what they are experiencing is always true and doesn't distinguish their experience within a course. Through dialogues like this, people discover that there is no definable behavior, emotion, or thought that confirms or disconfirms their participation.

Alternatively, we might invite people to see if they can "not participate" for a period of time. If they subsequently report that they disengaged from this work we might ask them how they did this. If they respond by saying, "Well, I just turned off. I let my awareness and vigilance lapse, and I got distracted in meaningless conversation with another participant", we might ask, "Were you aware that you were distracted?" If they say, "No," we might reply by asking, "Then how do you know you were distracted? How can you say you were disengaged from the work?" If they reply, "Yes," [they were] aware of becoming distracted," we might ask them how they could become aware of becoming unaware. In terms of their participation in the course they see that their capacity to observe that they aren't participating shows that they are actively engaged in the course. In this way participants discover that irrespective of what they tell themselves, there is no such thing as being engaged with, or disengaged from, this work. There is no such thing as being inside, or outside the course.

Another way we deconstruct the distinction between "doing" and "not doing" is to invite people to observe the discourses that transform "doing" into "not doing" and vise versa. What typically happens in a course setting is that certain activities, for example, group dialogs, conversations with facilitators and following specific instructions, are viewed as "doing it", while other activities, such as eating, sleeping, taking time out, etc., are viewed as "not doing it". We invite people to observe in real-time what is occuring that has them assess that they are now engaged, or disengaged, in this work. We focus on the windows, of five to ten minute's duration, during which these changes usually occur.

People become aware of the construction of importance and significance that precedes a group dialog, or individual session with a facilitator. They experience the construction of "getting ready" and the accompanying mood of expectation. They also track any dissipation of intentionality that often occurs immediately after a group meeting, and then observe the partial recovery of focussed energy that occurs when they begin to personally explore the generic discourses disclosed in the group meeting. The on-going observation of these modulations in thought, mood and atmospherics, deconstructs the assessments that people are engaged, or disengaged in this work. These observations introduce a sense of flow and continuity, such that people's involvement is no longer segmented into periods of "doing it" and "not doing it". People arrive a point where they really can't determine whether they are participating or not.

Deconstructing The Phenomenon Of Fixation

As we explained earlier, the observation and correction of fixations that is introduced as a preliminary phase in this work, only makes sense in the presence of a belief that we need to be doing, or not doing something, in order to achieve an on-going experience of clarity and contentment. While it might seem that this preliminary phase merely conditions the belief that we should be "doing, or not doing something"; in practice it deconstructs the phenomenon of fixation. The observation of pairs of extreme fixation deconditions the belief that things are right or wrong.

The exercise of observing fixation evolves beyond itself into a way of being and living that transcends the need to strategically employ any psychological or spiritual device to change or maintain one's present experience. This exercise transcends itself because as the belief that "something is missing" is gently deconstructed, this naturally attenuates the need to implement any exercise at all. As people refine this practice, there is less and less to hang onto. The need to employ some procedure dissolves in precise harmony with the effectiveness of its implementation. As such, this practice dismantles itself.

Engagement with the exercise of observing fixation opens out in such a way that they embrace everything that we can possibly think, feel, and do. They gently and imperceptibly take us to a point where there is nothing that we can do that is inconsistent with them. The practice is fully realized when people discover that there is no practice, or - what amounts to the same thing - that there has never been a time when they weren't fulfilling this practice. In the very midst of engaging with this preliminary exercise people discover that they aren't doing anything different from what they would otherwise have been doing. They experience the impossibility of practicing a method, as opposed to not practicing it. At this point ceasing a practice becomes indistinguishable from continuing with it.

Previously, practice consisted of a discipline that one could do, as opposed to not do - whereas now they experience that there is no such thing as practice, since there is no thought, feeling or behavior that is to be accepted or rejected. There is no special thing to do, or perform, that is different from what we are already doing. The guidelines simply describe what we are already and always doing. From this point of view we could just as validly say that everything is our practice, or that there is no such thing.

For example, people experience the impossibility of resisting, or giving into a desire; as distinct from being present to the thoughts and feelings that are manifesting at any point in time. Giving into, or resisting, one's desires, are experienced as assessments we make about what we should and shouldn't be doing. People see that there is no such thing as "giving into or resisting a desire". In the context of neither giving into nor resisting their desires, people see that the language of desire and aversion doesn't direct their behavior. They find themselves being in a way wherein they are neither giving into, nor resisting their desires.

People similarly experience the impossibility of holding onto their pleasures, or letting go of painful experiences. They are already neither letting go of, nor hanging onto, their experience. There is nothing else they could be doing. The notion of letting go of, or hanging onto an experience is simply a thought that accompanies an experience. They discover that they are already doing what they are trying to do in correcting fixation. They have accomplished the purpose of the guidelines without even needing to think about them.

Likewise, people experience the impossibility of dramatizing or trivializing their experience, since this assumes that there is something different that they could be experiencing. The suggestion is that we are making up something that isn't there, or ignoring something that is there. However, this discourse trades on the assumption that we can be experiencing something when we aren't, and that we can not be experiencing something when we are. It implies that there is something behind, or within, our experience that we are distorting. People experience the impossibility of distorting what they are experiencing. They are simply experiencing what they are experiencing. People similarly recognize that their experience isn't real or illusory for this distinction implies that we can have two conflicting experiences at the same time.

This new development comes as a result of seeing that the typography of fixation is a linguistic creation. People see that there is no characteristic that distinguishes an experience as "fixated", beyond a declaration that it is so. A thought, emotion or attitude that represents a fixation from one perspective, can also be experienced as a natural process that expresses the harmony and interdependence of our thoughts, feelings, and actions from another perspective. It is simply a matter of our interpretation. Similarly, there is no characteristic that can tell us that one action is emotionally neutral, whereas another is reactive. We reach a point where everything, or nothing, can be seen as a fixation. Outside of the standards we set internally, there is no reference system at all with which to make the distinction that some thoughts, feelings, and actions are fixated, while others aren't.

People similarly discover that there is no such thing as practice. There is only a description of an exercise, such as we have given. The notion of a practice is merely a conversation that is laid over the flux of our experience. "Practice" is a construction that we have "chosen" to do something "personally worthwhile". The standards that we set for assessing whether we are engaging well, poorly or not at all, are standards that only exist within the "discourse of practice" itself. They don't correspond to an objective, experiential reality. The whole thing is an elaborate (often externally corroborated) construction.

At this point people see through the construction of needing to become enlightened. They are no longer hell bent on urgently and radically transforming themselves. They are considerably less strategic and much more gentle in their engagement with what they are experiencing. As a result they are present, in an open and inviting way, to an ongoing flow of fresh sensations, emotions and ideas. The heavy judgements we have about what we should and shouldn't be feeling, dissolve; leaving us with a smooth, spacious and even-minded experience of being-in-the-world.

People realize that there is nothing they could do to enhance or destroy this experience. The experience cannot be cultivated because it isn't modified by any change in our thoughts, feelings, or behavior. Similarly, it is impossible to turn it off. Metaphorically, we can't go to sleep even if we'd like to. The experience is so acute and spacious that nothing is unobserved. Any attempt to fall unconscious fails because we can't help but see what we are doing. We watch ourselves trying to turn off or become unconscious by distracting ourselves in some trivial or meaningless activity, but our insight into the intrinsic meaninglessness of this and every activity renders it incapable of damaging or diverting our awareness. We are unable to trick or deceive ourselves any longer.

The space we are describing mustn't be confused with giving up a practice. It doesn't arise as a consequence of being loose or slack in observing fixations. What we are describing is totally different from ceasing to practice as a deliberate decision, or as a reaction to the challenge and possible discomfort of becoming aware of our thoughts, feelings and actions. Stopping presupposes that we could have continued. The act of stopping (or continuing) achieves nothing because we are still caught up in our fears and hopes about what could, or would, have happened if we had continued (or stopped). Whether we believe we need or don't need to practice, we are still trapped by the belief that practice refers to a real and objective activity. We are still inside the conflicting belief structure that we can or can't change our experience by continuing or discontinuing our practice. Of course, this space does not preclude the exercise of discipline, except here it isn't designed to consolidate or displace what we are experiencing.

Deconstructing Deconstructive Contemplation

Finally, we deconstruct the process of deconstructive contemplation because people can latch on to this as a new method for fixing, managing, or transforming their lives. Through participating in this work people can easily think they are engaged in a very unique process. They can't really compare the experience with anything else they have done. Very often they have never engaged in this type of thinking before, nor clearly seen how bondage and freedom are constructed. So they conclude that this work is special, profound, or esoteric. In other words, they construct deconstruction as a distinctive event. For example, people may think that they have actually deconstructed various psychological and spiritual discourses. They may think that their capacity to deconstruct psycho-spiritual discourses depends on a special tool called "deconstructive contemplation". In this way, contemplative deconstruction becomes a new form of practice. You might also be led to conclude that there is something in this discipline by virtue of having read twenty odd pages about it!

When this occurs, we ask participants what this "deconstructive contemplation" is, that they think has been occuring. They might answer that it is a refined process for uncovering and dismantling transparent beliefs that have structured and limited their lives. If this begins to occur, we disclose how a phenomenon called "deconstruction" can be constructed, just as we have done in this paper. In general terms, deconstruction is constructed on the assumption that within a fixed time-frame, certain belief structures have been disclosed that otherwise wouldn't have been disclosed. It is invoked as an explanation for how the disclosure was accomplished. But to say that "what was disclosed", wouldn't have been disclosed, were it not for the presence of deconstructive activity, is to claim the impossible, since it assumes that something different from what happened, could have happened. But, there never can be any evidence to demonstrate that what did happen, needn't have happened.

Similarly, to say that "what was disclosed", wouldn't have been disclosed in the absence of a clear disclosive space, is to construct that a disclosive space can be created. A disclosive space is the field within which all things manifest, persist, and decay, exactly as they do. Ultimately, it is indistinguishable from the experiential field. It is the occurence of that which occurs in it. We can't create this disclosive space since this is tantamount to creating the universe. As such, a course cannot create a disclosive space. A course occurs as an event within the disclosive space that precedes and follows it. (Just as reading this paper is continuous with what precedes and follows it.) Further, to the extent that there is never a time when there is no disclosive space (time being an occurence within it), it is a vacuous concept. In fact, the disclosive space that is disclosed doesn't exist.

In the absence of a disclosive space we cannot claim that a course creates privileged conditions for seeing through limiting beliefs. What transpires during a course in terms of conversations, feelings and private thoughts, is simply what transpires. In terms of reading this paper you have thought the thoughts you have had, and felt the feelings of interest, excitement, confusion, annoyance, etc. that accompanied them. If people are inclined to make this event into something special, then that is what occurs, and that is what is disclosed in this disclosive space. If people then slide into an opposite interpretation, and judge that this event has been trivial, or that there is no such thing as deconstruction, the slide is disclosed as yet another construction of what is occuring. If people are stuck in this intellectualization we may point out that without this work they would not be observing what they are now observing. In this way people see that deconstructive contemplation is neither something nor nothing.

David Brazier, Zen Therapy: Transcending the Sorrows of the Human Mind, New York: John Wiley, 1995

Cabezon, José. I., A Dose of Emptiness - An Annotated Translation of the sTong thun chen mo of mKhas grub dGe legs dpal bzang, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Chandrakirti. Madhyamakavatara. English translation in Peter Fenner, The Ontology of the Middle Way. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Pub. Co., 1991.

Cleary, Thomas. (trans.), Zen Essence - The Science of Freedom. Boston: Shambhala, 1989.

Conze, Edward., Materials for a Dictionary of the Prajñaparamita Literature, Tokyo: Suzuki Research Foundation, 1973.

Coward, H. and Foshay, T. (eds.), Derrida and Negative Theology Albany, State University Of New York Press, 1987.

De Martino, Richard, "The Human Situation and Zen Buddhism." In Eric Fromm, et. al., Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis, New York: Harper And Row, 1970, pp.

Epstein, Mark, "Meditative Transformations of Narcissism", The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 18.2 (1986), pp. 143-158.

Epstein, Mark, "The Deconstruction of the Self: Ego and "Egolessness" in Buddhist Insight Meditation", The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 20.1 (1988), pp. 61-69.

Epstein, Mark, "Forms of Emptiness: Psychodynamic, Meditative and Clinical Perspectives. The Journal Of Transpersonal Psychology, 21.1 (1989), pp. 61-71.

Epstein, Mark, "Psychodynamics of Meditation: Pitfalls on the Spiritual Path', The Journal Of Transpersonal Psychology, 22.1 (1990), pp. 17-34.

Epstein, Mark, Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective, New York: BasicBooks, 1995.

Fenner, Peter, The Ontology of the Middle Way, Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Pub. Co., 1991.

Fenner, Peter, Reasoning Into Reality - A Systems-Cybernetics And Therapeutic Interpretation Of Middle Path Analysis, Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1994.